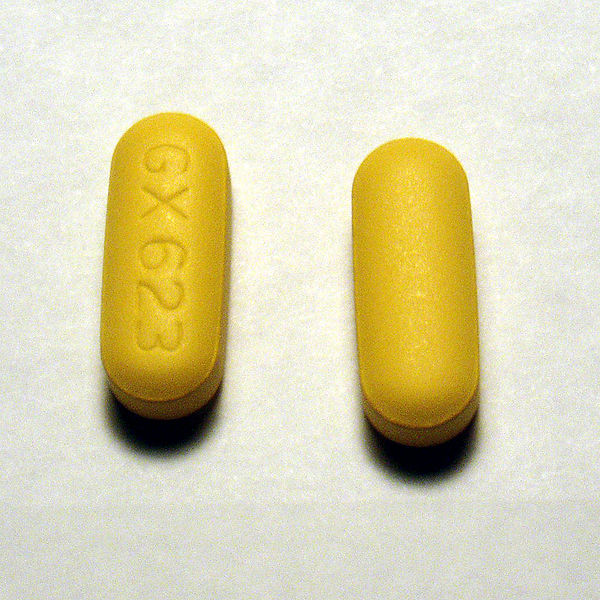

About a month ago, Nephron Power wrote about a great electrolyte case in AJKD. The case regarded a patient who drank a liter of methanol but was asymptomatic. The reason the patient was apparently resistant to a toxic methanol slug of methanol (The quantity of methanol that produces toxicity ranges from 15 to 500 ml of a 40% solution to 60 to 600 ml of pure methanol) was protective powers of abacavir. Abacavir is a nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor and apparently, is a potant inhibitor of alcohol dehydrogenase, the critical enzyme which converts methanol into formaldehyde. Formaldehyde is then converted into the lethal formic acid by formaldehyde dehydrogenase.

After reading this I started to wonder if abacavir was such an effective inhibitor of alcohol dehydrogenase what happens when patients get exposed to say a more common substrate of alcohol dehydrogenase such as whiskey. Shouldn’t we hear about people on abacavir going on alcohol benders after a single shot of ethanol?

A couple of cracks at PubMed and I sure didn’t find much. Barber, Marrett et al. looked for two types of alcohol reactions from abacavir, either a disulfaram-like reaction or reduced alcohol tolerance. The authors found three cases of in 173 patients starting abacavir. They found one disulfarem reaction (nausea, tachycardia, flushing with a single shock of vodka) and two cases of decreased alcohol tolerance

After three glasses of wine he felt as though he had a bottle and a half, with memory loss.

The only other paper I could find was by McDowell, Chittick, et al. who looked at increased abacavir levels with alcohol intake. The reverse of what I was looking for, but at least it was related. They gave a single dose of abacavir and 0.7 g/kg of ethyl alcohol to 25 HIV positive men. They found a 26% increase in the half life of abacavir with alcohol but…

This study did not demonstrate any alteration in the pharmacokinetic parameters of ethanol by abacavir coadministration; blood ethanol median profiles following ethanol administration in the presence and absence of abacavir were essentially superimposable. There was no evidence that co-administration of abacavir interferes with ethanol metabolism. There were no disulfiram-type reactions in any subject who received coadministration of abacavir and ethanol.

This study tested the effects of a single dose of abacavir, chronic dosing may result in a different effect on alcohol dehydrogenase.

Interesting case nonetheless.